Before the wall came down, in the eastern part of Germany, property didn’t play a significant role. Under communism, large properties were usually in the hands of the government, and private individuals didn’t own much. And even if someone did own, for example, a house, it could be more of a burden than a privilege, since building materials were often hard to come by—an issue caused by the planned economy, which frequently resulted in chronic shortages. As a result, people who owned real estate often couldn’t maintain it and sometimes even sold it to the government for a symbolic amount. Who would risk trouble because of falling bricks when maintenance was impossible?

So, did the government care about the houses it was responsible for? It didn’t. I remember growing up in an urban landscape that looked as if the war had just ended: bare brick walls without plaster, rainwater dripping from burst pipes, broken and rotten windows and doors. No, the government didn’t take care of the old buildings—resources were missing. Instead, it turned out to be cheaper to build new high-rises out of prefabricated concrete slabs than to maintain the old structures. Often, even tearing them down was too much. Whole neighborhoods in East Berlin, Leipzig, and Dresden were abandoned and turned into ghost towns.

This is why, in 1990, after the wall had come down, many of the tenement houses in East Berlin were abandoned government property. And once the Iron Curtain had been breached, after East and West Berlin could finally meet, something unexpected happened with these buildings. During those months between revolution and reunification, 1989 to 1990, many of the old and empty houses in East Berlin became free spaces—free of anyone checking who moved in, free of rent, free to live the life one wanted, independent of financial constraints. Young people from the East had already discovered these government-free spaces, and now squatters from West Berlin seized the opportunity as well. At last, there was a place free of both political and financial restrictions: East Berlin became the Eldorado of squatting.

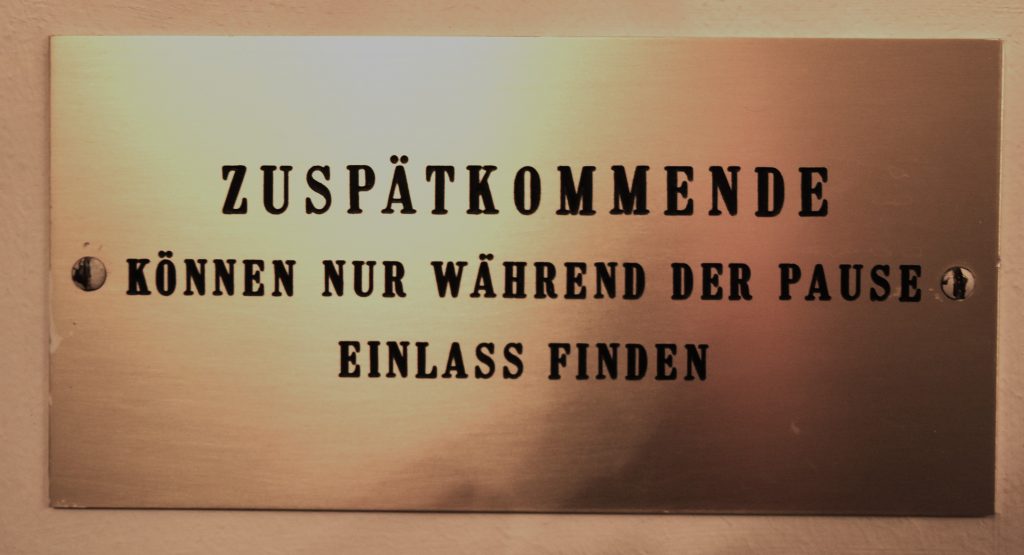

That is more than 25 years ago. Since then, things have changed. The real estate market has become big business, and properties have been assigned to new owners. The “housing initiatives” were pushed out, often after years-long legal battles, and not seldom with massive police operations. Today, only one place remains: “Köpi” (see picture above), named after its address on Köpenicker Straße. Just last year, the latest attempt by the real estate company currently owning the land to evict them failed in court.

These initiatives have often been fertile ground for creativity: exceptional art projects, theaters, music, and unforgettable parties. At the same time, it is clear that Berlin benefits from international investment, as seen in the example of “Mediaspree” (see picture below), a property development project along the riverbanks of the Spree, the river flowing through Berlin. These projects create numerous jobs and generate tax revenue. In other words, it is naive to “fight capitalism” when it is difficult to name a workable alternative. And yet—the creativity that has flourished in free spaces like Köpi has been one of the major reasons for Berlin’s reputation as a center of freedom and artistic experimentation in Europe.

So the question remains: How can a city protect the freedom that fuels its creativity while still relying on an economic system that threatens to erode exactly that freedom?

Good memories, Carol, thank you for that. Yes, being a guide was a true prvilege and I appreciate you paying…

Hello Bernhard My husband and I were in Berlin several years ago with friends and you were our tour guide…

Beautiful monuments and scenery! ❤️

Than your for the comment!

In fact the pictures take more time than anything else - I appreciate the comment!